|

|

|

| A photo diary: the passing days of a grape

harvest in rural France. These photos chronicle 12 days of harvest

at the vineyards of Aubert & Pamela de Villaine in the village

of Bouzeron in the Côte Chalonnaise. The harvest usually

begins in late September, the date coming more or less one hundred

days after the flowering of the vines in the early summer. |

|

| For the harvester, the workday begins at 7:45am

and ends around 6:00pm. The days are spent working in teams

up rows of vines one plot after the next. The mornings are cold

and the afternoons are often warm. In the trucks that carry

the workers to the vines lies a pile discarded sweaters and

coats. |

|

| The anticipation of the lunch break and dinner

is fueled by occasional bottles of the wine and water passing

between the vines. Before lunch, we wash the mud from our clothes

with a garden hose. Lunch invariably includes a meat stew, wine,

cheese and fruit. Conditions when the foreman is most eager

to get back to work: impending storms, late starts, troubles

with the tractors. |

|

| It matters to have good rubber gloves, good

clippers and interesting co-workers. Although each day is long,

one falls into the next. In a routine of working between the

vines buried in one's thoughts, rising up to see the wide vistas,

stopping for conversations, water or wine, or sharing songs

and words between the grape leaves, the fortnight can begin

to seem like a single long day. The day is punctuated by highs

and lows, shifting moods, and changing weather. |

|

At the moment he announces the harvest,the

winemaker is gambling with nature. Bring forty harvesters to

your property too early, you pay for them to sit about; if they

come too late, you might lose the harvest to rain or hail. The

problem is complicated by growing three different varieties

– Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, and Aligoté – which

ripen at different times. Hail in the next village is ominous:

for winemakers just over the crest of the hill, the hail has

caused the loss of a year's work.

|

|

| Although the Aligoté is the most important

grape in this vineyard, it ripens slightly later than the other

varieties that are growing. First to come in is the Chardonnay,

then the Pinot Noir. The order of cutting is a question of ripeness,

value and practicalities. The grapes cannot all be cut in one

day. |

|

| In cutting the reds, one must watch carefully

to spot ripeness and rot. A sour taste will tell, but it will

also pucker the mouth. One looks for the light pink or green

showing through the skins. |

|

|

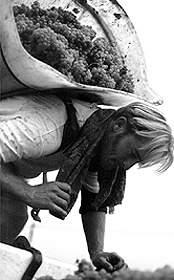

| Gloves wear through quickly. Without them,

the sugary moistness of the grapes helps to bring on blisters.

The gloves, clippers, and grapes become intimate objects –

extensions of the flesh. |

|

| With tough, tannin-rich skins, the grapes

taste a little bitter. To make a good wine they must offer a

balance of acids and fruit sugars. The aromas and flavors of

the wine to be made exisit now only as potential. In harvest,

it matters that the grapes arrive at the winery undamaged and

as soon as possible after they are cut. |

|

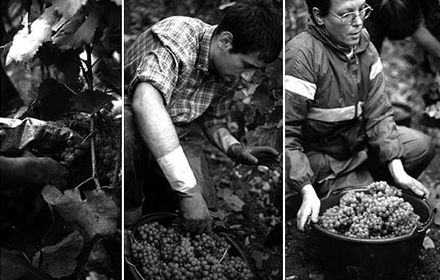

| The grapes pass from the vines to buckets,

from the buckets to panniers, from the panniers to tractors,

from the tractors to the winery. How much care the grapes receive

at each stage is mediated by cost. The choices are determined

by the market value of the wine that the grapes of a particular terroir can produce. |

|

Tasks are assigned and repetitive. The pickers

select the grapes: Red grapes should not be cut too green,

or with too much leaf. Rotten grapes should be cut away. At

the tractor, the foreman eyes the quality of the grapes. The

porter who has carried the grapes to the tractor may return

to the harvesters in his team with instructions or admonitions. |

|

| Best are the tiny concentrated grapes of older

vines whose roots reach far into the bedrock where they extract

richer mineral content. Vines become worth harvesting after

about four years and can produce good yields for fifty or sixty

years – a human's lifetime. The unique quality of time

felt during the harvest is set against the long history of the

vines and the culture supporting them – vines are planted

for lifetimes and across generations. |

|

| We, too, come from various generations. There

are mothers and their daughters, cousins, immigrants, returning

workers, local friends, and students. A number of local factory

workers, once connected to the vineyard, join the harvest for

the festive first day. A couple from Poland who met here at

a harvest over a decade ago when the money mattered more, now

come each year for a working holiday. |

|

| At the dining table there is

a kind of weary revelry. In work, there is little time to stop

or reflect on the action at hand. The dining tables are in a

cavernous room beneath the house and dormitories. The room is

dark and comforting to eyes that have come in from hours in

the sun. The space is damp and has a rich smell of the meat

stews we are served. |

|

|

| The soft, thick and crumbling stone walls

fall into darkness illuminated only by the small beams of light

that come from the door and small deep windows. In the vines

we begin thinking of lunch ahead. In the dining hall, there

is a desire to remain suspended between the memory and anticipation

of the work outside. |

|

| Visually, when one is working in the vines,

the world seems either very near or very distant; it is a world

of close-ups and landscape vistas. The presence of the fellow

workers comes by way of the sounds and conversations which pass

through the thicket. You feel your body in parts: your hands,

your knees, or your back, and you catch the occasional glimpse

of other workers in fragments through the leaves, posts, and

wires. |

|

|

...THIS IS THE END OF THE SAMPLE ... BUT THE HARVEST CONTINUES.. |

Please visit www.eastgate.com to see the full work...

|

. |

|

|

|

|

|

Recognitions are a photo's proposition: a sense of peace in the vines,

the urgency of a boss, the forms of faces in changing light, the halting

of time as the harvesters rest and regard the view at the end of a row

of vines. Movements

are arrested, their narrative directions are like vectors – the stories

are not yet determined. Against the (e)motion of stillness and the seeming

timelessness of lunch hours in the winery caverns, I recall the immediacy

of carrying a pannier full of grapes and the pressuring shouts of Jean-Louis,

the harvest foreman.

|

| Shuffling these photo documents into

differing orders, I find myself reinventing a series of pasts in the

hindsight of narrative. Organizing the photos in a row reminds me

of comic strips, of the slide strips of old viewing machines, of film

storyboards, and of dream recollections where the conjunctions between

images have slipped from memory. Jumping back and forth, patterns

emerge of alternative stories. |

The

focus shifts to the space between the people and the landscape

views – to the enveloping world of vines, grapes, posts and soils.

Angles by which I viewed people resemble others I took of objects. |

|

The histories of people differ from those of images

which direct the eye to see continuities and contrasts. Such pictures

describe relationships between one person and another or between people,

the objects they use, and spaces they occupy. END OF SAMPLE.... WORK CONTINUES... |

|

|

|

|

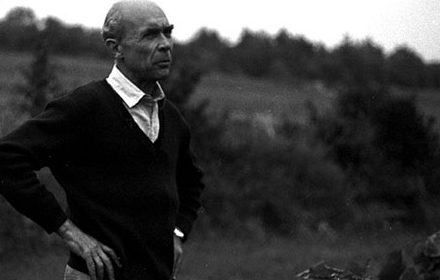

In the vines one day, Aubert de Villaine tells me that

for him, "Wine is an image," by which he means,

as he goes on to say, that each aspect of winemaking is

part of a process of working toward an ideal form.

The image, he tells me, is "based on the wines that

he has known in the past." His goal is to make wine

in ‘the simplest ways possible’ to yield a product

that is pure. |

|

|

This "image" of the wine is a reflection of Aubert's

taste, memory and knowledge of what different soils, grapes

and conditions might provide.It is a reflection of cultural

ideals he holds about balance, structure and elegance. As other

winemakers would repeatedly tell me, a wine is a reflection

of the character of the maker who has envisioned and produced

it. |

|

Aubert and Pamela moved to Bouzeron in 1970. Although winemaking

was introduced to this valley by the church in the middle ages,

the vines had been since abandonned. When Aubert and Pamela

arrived there was little winemaking here. However, through research

in the archives at Macon and elsewhere, Aubert discovered that

the valley had a history of winemaking and was once particularly

known for the white Aligoté. |

|

|

Following the deadly outbreak of phylloxera, a pest native to

North America that destroyed most of the French vineyards at

the end of the nineteenth century, the area around Bouzeron

was, for the most part, not replanted. This was probably because

the land here is less suited to the more popular Chardonnay

and Pinot Noir vines that were being planted in other areas

to the north on the Côte d'Or, some of which had also

been previously recognized for their Aligoté production. |

|

The classification of the terroir and its wines is achieved

through a system of ranking known as the Appellation d’Origine

Contrôlée (AOC). The ranks include regional wine

designations such as "Bourgogne Aligoté," village

specific appellations, premiere growths, and grand cru. These

rankings, developed in the 1930s, are based on expectations

of what differing terroirs can produce. |

|

Even the greatest Aligoté is a modest wine when compared

to the famous grand cru Chardonnays and Pinot Noirs of the Côte

d'Or. Aubert's vision of his wine is based on what he believes

a terroir can yield. His role is to assist in a natural process.

This includes moderating negative forces, such as those of frost

and mildew, which can diminish the health of the vine and the

positive qualities of grapes. The vision is also based on how

he envisions the work and the world he builds for himself. To

make wine, Aubert

once remarked, you always stand before a white sheet, not

knowing what nature has in store for you. In this way you are

both the maker and marionette. |

|

|

The AOC sets requirements such as varietal percentages and minimum

sugar levels such that a wine grown on grand cru soils might

not obtain its grand cru status on a particularly poor year.

At Bouzeron, Aubert worked with the other winemakers to gain

AOC village status, the only such status in France for the Aligoté.

Around the village of Bouzeron the soil is particularly poor.

De Villaine believes this helps intensify the flavors of the

Aligoté which is a vigorous vine. At the same time the

conditions are more challenging than the Côte d’Ort;

an ideal image of a wine co-exists with that determined by temporal,

economic, or even cultural circumstances. |

|

Aubert arrived in Bouzeron with extensive experience in the

issues of making grand cru wine. He followed his father as a

co-owner/winemaker at the famous Domaine de la Romanée

Conti in Vosne-Romanée where he continues to make grand

cru Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. Making a wine in the less established

valley of Bouzeron presents a different set of challenges, such

as a more frequent risk of frost, and less options in solving

problems because the price that local wine can fetch will not

support the use of expensive technologies. |

|

Aubert sees himself as participating in a long history of winemaking.

He reads logs from past winemakers to learn about prior knowledge

of the terroir and climate conditions and he writes notes of

his own experiences over time. Along with developing the Bouzeron

Aligoté, Aubert has been a force in promoting a regional

identity for this area south of the prestigious Côte d’Or

under the name of the Côte Chalonnaise. Its vineyards

stretch across the hills above the Soâne between Chagny

and Chalon-sur-Soâne to include towns such as Givry, Mercurey,

and Rully. |

|

... END OF SAMPLE ... "The Harvest" CONTINUES in the CD-ROM CULTURES IN WEBS...

Please visit www.eastgate.com for the full work...

|

|